It’s high time for time travel! Time travel?! Isn’t that about other dimensions and wormholes? Not anymore! 120 something years after H.G. Wells popularized time travel in his science fiction book The Time Machine, the notion has fully and forcefully entered the realm of urban historians. In most scifi stories, people travel to the future, but traveling back in time may be just as exciting. Who wouldn’t want to find themselves smack in the middle of Golden Age Amsterdam, attending a bullfight at the San Marco in Venice, or visiting bustling fin-de-siècle Paris in the 1920s? In a few years from now, what seemed like science fiction will become (virtual) reality.

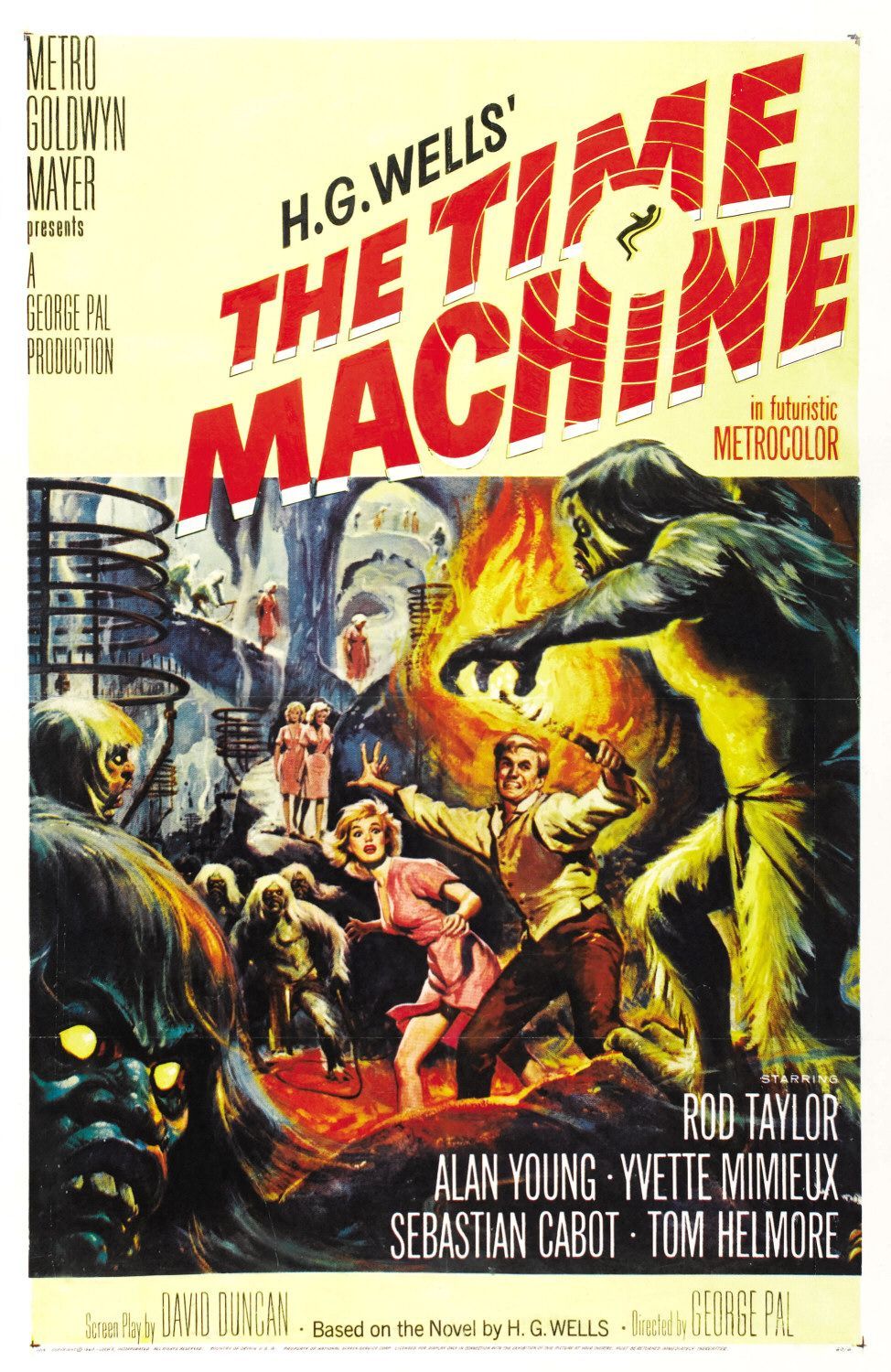

As we speak, humanities scholars and computer scientists, as well as professionals in creative industries and cultural heritage are joining forces to build times machines for these and other European cities. What we call time machines looks less like the car in the 1960 film of The Time Machine, and more like a web of URI’s and algorithms that, for instance through machine learning techniques, allow for scanning, linking, searching, analyzing, and presenting historical information. Digitized information on sites, people, events, businesses, and objects will be linked and represented through maps and 3D models (even 4D once we add the dimension of time!). The local time machines will in the future be linked so that they can reveal in extraordinary detail how trade flows, migration, and knowledge exchange developed over time and across (and beyond) Europe. According to Frederic Kaplan, such a European Time Machine would serve as a Google and Facebook for generations long past (do check out his TED talk!). Kaplan is head of the first Time Machine (Venice), driving force behind the European Time Machine consortium, and director of the Digital Humanities Laboratory at the Swiss Federal Institute of Technology in Lausanne (EPFL).

Between all the data on Amsterdam that is digitally available and all the local historical expertise, it is certainly possible develop our own local time machine – or so a group of researchers and heritage data experts figured after learning about Kaplan’s project on Venice. This year, they will start for real, as various projects received funding from NWO, CLARIAH, and Stichting Pica. At Huygens ING and University of Amsterdam a project will start on local cultural industries in the Golden Age; a project at the University of Amsterdam will also enable search and linkage functionality on the minutes of the city council; a larger consortium will expand the HisGIS mapping infrastructure of historical maps; and AdamNet has already started to link datasets from its 33 local heritage partners.

One of the cool things about the Time Machine is that it brings all kinds of people and projects together. Collections of images, objects, texts, audio, and video of local archives and museums, as well as historical research data gathering dust on outdated servers, will be connected through linked open data. A major added value of the time machine lies in its potential to connect data from all these different (kinds of) sources and thereby facilitate multidisciplinary research. The Time Machine infrastructure makes it much easier for users to look at, for example, patterns in artistic production and consumption while systematically taking into changes in the broader urban environments. Computer scientists, moreover, are eager to use all our fuzzy historical data to test and train their algorithms to learn to take complexity and uncertainty into account. The linked data should be open and the techniques open source, so that they can be taken up by creative industry businesses who develop apps and Virtual Reality technology to engage wider audiences in historical narratives and experiences. Tourists may to visit Rembrandt in his studio or witness the transformation of Dam Square. Locals may want to see what their houses looked like before or find out who lived there. And through crowd-sourcing they can even partake in such reconstructions of local histories.

Surprisingly (or perhaps not…) many historians are most skeptical about the digital turn and all this possible time traveling. I believe, however, that time machines should also be on the top of urban history’s wish list. Charles Tilly has described the city as the “privileged site for study of the interaction between large social processes and routines of local life” (Explaining Social Processes, 2015: 161). Times machines provide exactly the kind of infrastructure that can bring this interaction into focus. We can go back and forth from the micro to macro level, as the infrastructure allows us to identify individuals and their life courses, but also reconstruct social networks or mobility patterns. We will be able to zoom out on the level of the entire city or specific neighborhoods or zoom in on streets, houses, or even on the pictures that adorned the walls of a seventeenth-century merchant or a nineteenth-century industrialist.

The Amsterdam Time Machine is coordinated by the research program Creative Amsterdam: An E-Humanities Perspective (CREATE). All parties have different pieces of the puzzle and something to gain. Not tied or governed by individuals or single institutions such universities, heritage institutions, the collaborations in the Amsterdam Time Machine form their own governance model. The group has been growing and meeting regularly since early 2017, laying the foundations and developing sub-projects. Our network is open-ended, so feel free to join us if you have data, tools or ideas to add to mix!